by Rob Morse

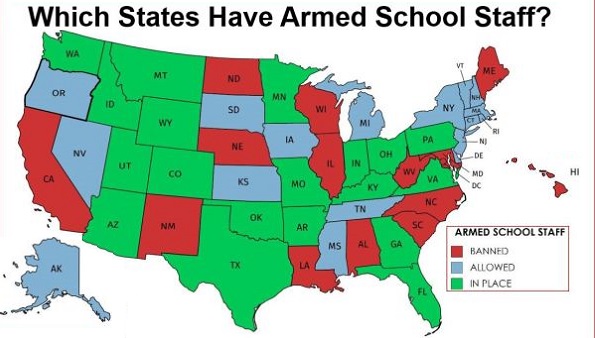

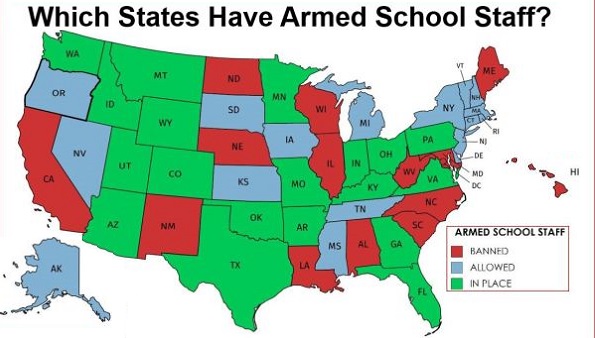

School is about to start. Does your local school have trained first responders? Does your state allow selected and trained school staff to go armed in order to protect your children? I study those trends across the country. One thing I can tell you for sure is that my observations today will be inaccurate next month. I’ve revised this map several times this year. While I can find public announcements in most cases, some states do not require the public to be notified if school staff are armed. That uncertainty skews my research, but too bad. There are excellent reasons not to publicize school security plans. I’ll gladly accept that uncertainty even if the resulting data underestimates the number of states and schools with armed staff.

Some states allow armed school staff and some state governments clearly deny it. The issue of legal permission or prohibition becomes more complex as we look closer. The line is blurred rather than clear-cut. Some states allow armed staff for private schools but deny it to public schools. In addition, some sheriffs go to great lengths to enable selected school staff to be armed.

While that is a good thing, it means it may take extraordinary legal efforts by a sheriff and a local school board to have armed first responders defending their students. That level of effort may not be available to every school board in the state.

Where are we today?

Ohio allows armed school staff at the discretion of local school boards. Most, if not all, of these school boards use the FASTER training program. I contacted the volunteers at FASTER to get a feel of the size of their activities to date. FASTER has trained more than 1000 school staff members to be armed first responder. About a hundred more have been trained in Colorado.

The movement to arm school staff went into high gear after the murder of our students in Sandy Hook, Connecticut. The program has been ongoing for 5 years, and that is long enough for some of the trained staff to retire or change schools. We’ve gained a lot of experience even with those losses from the program. The FASTER program has accumulated thousands of man-years of experience with trained first responders in the classroom. That underestimates what we know. Several states, like Utah and Colorado, allowed armed school staff for years before the attack at Sandy Hook. Utah does not require the concealed carriers who work at schools to notify the school administration if they are carrying.

Looking at the numbers, 82 of the 88 counties in Ohio have programs with armed school staff. 20 percent of the staff in some rural Ohio schools are trained to be armed defenders and medical first responders. We call them “teachers”, but classroom instructors only make up 40 percent of the school staff trained by faster. Those teachers protect our kids even if the teacher in your child’s classroom isn’t armed. A murderer never knows which district, which school building, and which classroom is ready to stop him.

A known product

Districts used to investigate the FASTER program by sending a teacher and an administrator to take the training. These staff members would report back to the school board with their evaluation. We see less of that today. FASTER is now a recognized program and a known commodity. School districts adopt the plan after talking with superintendents and sheriffs from other counties. Today, districts adopt the plan by sending dozens of staff members for training.

FASTER used to collect private funding to pay for the first trained teachers and administrators. That is less common, although it still happens. Districts now budget for and pay to send a full complement of staff. Some districts fill an entire training class; usually two dozen students a time. The program is popular. When new training dates become available, class registration with openings for 24 trainees typically fill up in a day.

That describes the training in Ohio. Statistics from other states are harder to find. FASTER Colorado brought their training program to that state two years ago. 30 out of 181 school districts have a program for armed staff in Colorado today.

School staff come from other states to attend the FASTER classes offered in Ohio and Colorado. I know there are plans to start training classes in other states next year, but that has not happened yet.

The perception of armed staff has changed among school boards and teachers. Volunteers used to be selected from the staff who already had their concealed carry permits. Today, we’re seeing more teachers who will get their carry permits specifically so they may become armed school staff. That was unheard of a few years ago.

Medical first responders

The decision to arm school staff may make it into the local news. In contrast, the decision to train and equip school staff to perform emergency trauma care often goes unreported. School districts usually wait for summer vacation to train teachers to go armed. Rather than taking months, school districts can train medical first responders by next week.

A growing trend in the last few years is for districts to sponsor local medical training classes. That way, many staff members are available to treat the injured in an emergency. State government in Ohio provided matching funds for medical first responder training and for trauma kits. The goal was to have several trauma kits along every hallway.

Programs in churches

The progress in church security is several years behind what we see in schools. Fortunately, there are fewer legal restrictions on religious institutions. Church governing boards have greater latitude in adopting a first responder program. That freedom is both a blessing and a curse. There is a trend for churches to over-customize their security plans whereas most schools tend to adopt existing plans with a minimum of changes.

Disturbing issues

Political concerns are always with us. We see this in schools, churches and hospitals. Politicians and administrators reinvent the first responder training curriculum for their own political purposes. Administrators signal their virtue by demanding higher training standards for their staff. This reduces the number of first responders who are available and drives up costs. More importantly, it drives up the response time until a good guy can stop a bad buy. When seconds count, the injured will have to wait longer to receive treatment.

We’ve run enough exercises to separate fact from theory. It is better to have 10 staff members who each have 10 hours of medical training than to have a single responder who has 100 hours of training.

Some school administrators approved an armed responder program but dictated that firearms must be kept in a locked safe located in the classroom. That raises several questions. Why should students be unprotected in the parking lot, the amphitheater, the cafeteria, the gymnasium or the administrative offices? If a locked safe is a bad solution for police and uniformed school resource officers, then why is it a good solution for teachers? The experts say that on-body carry is best. If school staff must keep their guns in a school safe, then give them a carbine and body armor as well.

Political concerns are real. Maybe an incremental approach is all that the community will tolerate today.

Trends

Very few parents had ever heard of a school safety plan five years ago. Today, more parents are attending school board meetings and asking if their school safety plan is up to date. They ask when their school had their last safety audit and if the audit recommendations were fully implemented. I expect that trend to continue.

Community involvement is a driving force to make our schools and churches safer. More parents, teachers, administrators and sheriffs are determined to protect our children. More ministers say, “I will protect my flock.”

Through the miracle of this American experiment, these concerned people find each other and act. I’ve seen these citizen-volunteers collect the best solutions from around the world. That fills me with hope and with pride. I expect that trend to continue.

I hope you are part of it.